The Challenges Facing the NHS

Preparing for a medical school interview in the UK means understanding the challenges facing the National Health Service (NHS) today. Interviewers often ask about current issues in healthcare to gauge your awareness, insight, and commitment. In this guide, we’ll explore the major challenges confronting the NHS – from ambulance and A&E waiting times to cancer treatment delays and staffing shortages – all in clear, simple British English. We’ll also explain key terms and provide example interview questions to help you practice. By learning about these issues, you’ll be better equipped to discuss them confidently and thoughtfully in your medicine interviews.

Ambulance Waiting Times and Emergency Response Delays

Ambulance services have been under intense strain. Emergency response times have worsened, especially for Category 2 calls (serious emergencies like suspected strokes or heart attacks). The target for Category 2 ambulance responses is 18 minutes on average, but in late 2022 the average wait was over one and a half hours. Although response times have improved since that crisis point, they are still well above the targets in many areas. These delays mean patients with urgent conditions wait far too long for an ambulance – a situation that can be life-threatening.

The causes of long ambulance waits include high demand, crew shortages, and delays handing patients over to crowded hospitals. Often ambulances get stuck queueing at A&E (Accident & Emergency) because emergency departments are full and can’t take new patients. In some cases, patients in urgent need have even resorted to driving themselves to hospital. In 2023, over 500,000 seriously ill people in England had to make their own way to A&E because an ambulance did not arrive in time. Paramedics and doctors warn that these “Uber ambulance” situations are dangerous, as patients may deteriorate or risk injury when travelling unassisted. Reducing ambulance waiting times remains a top priority for the NHS, as timely emergency care is critical to saving lives.

A&E Overcrowding and Long Waiting Times

Britain’s hospital A&E departments (Accident & Emergency, or “casualty”) are facing severe overcrowding. The NHS has a target that 95% of patients should be seen, treated, and admitted or discharged within 4 hours of arriving at A&E. In reality, performance has fallen far short of this standard. In December 2022, about 50% of A&E patients waited more than four hours – an all-time high. Conditions have improved slightly since then, but as of September 2025 around 38.9% of patients were still waiting over 4 hours in major A&Es. That means well under two-thirds are seen within the 4-hour window, far below the 95% goal.

Long A&E waits are more than just an inconvenience – they can be dangerous. When patients crowd corridors for hours, clinicians worry that those with serious conditions might deteriorate before being treated. Trolley waits (waiting on a stretcher after a decision to admit to a ward) have surged as well. In January 2024, for example, 177,800 patients in England spent over 12 hours in A&E from arrival to being seen – that’s roughly 1 in 10 patients waiting at least half a day in emergency care. Even measured from the decision to admit (a narrower definition), over 54,000 people waited 12+ hours on trolleys in a single month, matching record levels. Clinicians call these delays “catastrophic”, warning that once waits stretch beyond about 6–8 hours, patient mortality risk increases.

The reasons behind A&E overcrowding are complex. High patient demand – especially from an ageing population – has increased attendance. But a key issue is exit block: many A&E patients can’t be moved to hospital wards because beds are already full. Hospitals have been running at very high bed occupancy (often over 90% full) since the pandemic. A major factor is the shortage of social care support for medically fit patients – thousands of people remain stuck in hospital simply because there is nowhere for them to be safely discharged to (for example, no care home placement or home care package available). This creates a bottleneck: A&E beds and corridors fill up with patients waiting for ward beds, and incoming ambulances then queue outside because A&E has no space. Workforce shortages (discussed below) also mean fewer staff to see patients quickly. All these factors contribute to the long waits. The government and NHS have launched initiatives – from opening extra “virtual ward” beds to offering same-day emergency care – to ease this crisis, but A&E performance remains a serious challenge.

Cancer Treatment Delays and Waiting Times

Cancer treatment wait times (England). The NHS target is for 85% of patients to start cancer treatment within 62 days of an urgent referral. In recent years performance has hovered around 60–70%, meaning roughly 30–40% of patients face delays beyond two months. Timely cancer care is critical, yet the NHS has been missing its cancer waiting time targets for years. The key standard is that at least 85% of patients should begin their first cancer treatment within 62 days of an urgent GP referral (the “two-month rule”). Unfortunately, this **85% target has not been met since 2015】. In August 2025, for example, only 69.1% of patients started treatment within 62 days of referral. In other words, nearly one in three cancer patients had to wait longer than two months to begin treatment. This is well below what is expected, and such delays can impact patient outcomes because cancer can progress while waiting for therapy.

Several factors have contributed to these cancer treatment delays. The COVID-19 pandemic significantly disrupted cancer services – diagnostics like endoscopies and biopsies were postponed, creating a backlog of patients. Even as services resumed, staff shortages and limited capacity (for surgeries, chemotherapy, etc.) meant the NHS struggled to catch up. As a result, tens of thousands of patients nationwide have experienced waits longer than the 62-day standard. For instance, by early 2023, the NHS was routinely missing not just the 62-day target but also the goal of seeing 93% of suspected cancer referrals within 2 weeks. The NHS has since introduced a new set of cancer wait standards (as of October 2023) – including a 28-day diagnostic rule – but performance remains below targets for all of them.

It’s important to note the human impact behind these numbers. A delay in cancer diagnosis or treatment can cause enormous anxiety for patients and families, and in some cases may allow the cancer to advance to a less treatable stage. The NHS is taking steps to improve cancer care timeliness: investing in new diagnostic centres, recruiting specialists, and expanding screening programmes. Still, recovering cancer waiting time performance to pre-2015 levels is a major challenge for the health service. Interviewers might ask about this issue to see if you appreciate why prompt cancer treatment matters and how the system could balance speed with quality of care.

Record NHS Waiting Lists for Routine Treatment

While emergency and cancer waits grab headlines, the NHS is also struggling with record-high waiting lists for routine operations and clinics. This refers to planned, non-urgent treatments – for example, hip replacements, cataract surgeries, or even initial specialist appointments. As of late 2023, around 7.7 million patients in England were waiting for hospital treatment, the highest number ever recorded. By August 2025 the list was still about 7.4 million – roughly one in eight people in England. For context, before the COVID-19 pandemic the waiting list was about 4.5 million, so the backlog has nearly doubled in five years.

The NHS has a constitutional standard that 92% of patients should receive their treatment within 18 weeks of referral (the 18-week RTT target), but this hasn’t been met since 2016. In fact, millions of people are now waiting well beyond 18 weeks. As of August 2025, about 2.9 million patients had been waiting over 18 weeks for elective treatment. Long waits of over a year, which were once rare, have become more common: around 190,000 people in England had waited more than 52 weeks for treatment at that time. Some patients even wait over two years for certain procedures, though the NHS has been trying to eliminate the longest waits by directing patients to alternate providers or regions.

This backlog has a number of causes. During the pandemic, many non-urgent operations and appointments were postponed, and fewer patients came forward (or could be seen), which created a huge pent-up demand. Since then, hospitals have been working through this backlog, but they face capacity constraints – including the same staffing and bed shortages discussed elsewhere. Operating theatres can’t run at full tilt if there aren’t enough surgeons, anaesthetists, nurses, or if beds are occupied by patients who could be elsewhere. Diagnostic tests like MRIs and endoscopies have also seen long queues.

Waiting a long time for treatment can significantly affect patients’ quality of life. Imagine someone in chronic pain awaiting a knee operation, or a person with hearing loss needing a cochlear implant – delays mean prolonged suffering or disability. The government has set targets to gradually reduce the backlog (for example, aiming to eliminate waits over 65 weeks, and improve the 18-week performance to 65% by 2026). Innovations like “surgical hubs” (specialist centres focusing on high-volume surgeries) and extended hours are being used to increase throughput. Nonetheless, the waiting list challenge is likely to persist for years. Demonstrating in your interview that you understand both the scale of the backlog and its impact on patients – and maybe mentioning the efforts to tackle it – will show a well-rounded awareness of NHS pressures.

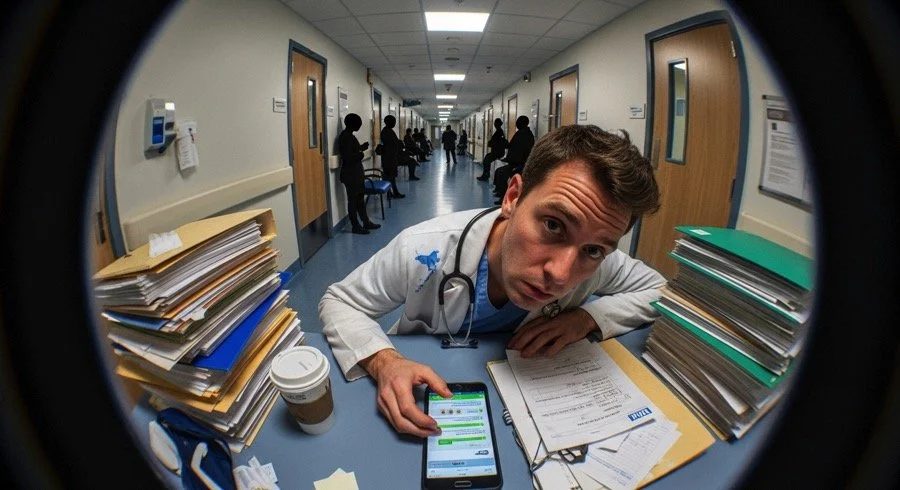

Staffing Shortages and Workforce Pressures

Perhaps the most fundamental challenge facing the NHS is the workforce crisis. The health service relies on its people – doctors, nurses, paramedics, allied health professionals, carers and more – yet there are not enough staff to meet the growing demand. Chronic shortages across primary care, hospitals, and community services have led to heavy workloads, burnout, and gaps in services. Below we break down some key workforce issues (in simple terms) in different parts of the NHS:

Primary Care (General Practice): General Practitioners (GPs) are the frontline doctors in the community. Despite government pledges to increase GP numbers, the overall number of fully qualified GPs has actually fallen in recent years. In 2015 there were around 29,300 full-time equivalent GPs in England, but by 2022 this had dropped to about 27,900. As of September 2025, there were still 849 fewer fully qualified full-time GPs than in 2015. Meanwhile, patient demand has risen – about 7 million more patients are registered with GPs now than in 2015. The average GP is now responsible for 2,241 patients, which is 304 more patients per GP than in 2015. This means GPs are stretched thinner, making it harder for patients to get appointments. Many GP surgeries report vacancies and have trouble recruiting new doctors. Workload pressure (administrative tasks, complex patient needs) leads some GPs to reduce their hours or retire early, further worsening the shortage. This is why you might have heard about patients saying “it’s almost impossible to see a GP” – there simply aren’t enough GPs for the population’s needs, and it’s a serious NHS challenge.

Secondary Care (Hospitals): Hospitals are also short-staffed. The NHS has thousands of vacant doctor and nurse posts in hospitals across England. As of mid-2025 the official vacancy rate was about 6.9% of NHS jobs unfilled – roughly equivalent to tens of thousands of positions. In particular, there were over 10,000 vacant medical posts (hospital doctor jobs), about 6.2% of the doctor workforce. Nursing vacancies have been even higher: in late 2023, NHS England had 42,300 nursing vacancies – about 1 in 10 nursing roles unfilled. These shortages mean existing staff must cover extra duties or wards may operate below ideal staffing levels. The UK also has a relatively low number of doctors per population compared to other European countries. England has only about 3.2 doctors per 1,000 people, which is lower than many peers (the EU average is ~3.9 per 1,000) – by one estimate England would need around 40,000 more doctors to reach the same doctor-per-person ratio as countries like Germany or France. Hospital staff shortages have been exacerbated by factors like Brexit (reducing EU nurse recruitment), COVID-19 burnout, and inadequate training numbers in the past. The result is that NHS staff are under severe pressure – for example, surveys show high levels of stress and burnout, and in recent years many NHS workers (including junior doctors and nurses) have taken strike action over pay and conditions. Ensuring a sustainable workforce is a huge challenge for the NHS’s future.

Social Care: The NHS does not work in isolation – it is tied closely to the social care sector, which provides support for the elderly and disabled (through care homes, home care, etc.). Social care in England is facing a staffing crisis of its own. There are over 130,000 vacancies in adult social care jobs, with care providers struggling to recruit and retain carers due to low wages and demanding work. Though recently international recruitment has helped slightly reduce the vacancy rate, the gap remains large (about an 8% vacancy rate in social care, higher than in the NHS). Why does this matter for the NHS? Because when social care is understaffed or unavailable, patients who are medically fit for discharge often cannot leave hospital (there’s no safe home or care facility for them). This leads to so-called “bed blocking” – thousands of NHS hospital beds occupied by people who don’t need medical treatment but do need care support. That in turn prevents new patients from being admitted from A&E, causing backups throughout the system (as discussed earlier). So, the social care staffing shortage directly worsens NHS waiting times. A long-term fix would require significant government investment and perhaps reforms in social care – an issue frequently debated in health policy.

Dentists: A part of the NHS often forgotten in general discussions is NHS dentistry. There is a mounting shortage of NHS dentists willing to take on NHS patients. Many high-street dental practices have either left the NHS system entirely or limit their NHS services, due to funding and contract issues. The Public Accounts Committee in 2025 reported that only around half of the population can access an NHS dentist over a two-year period under current arrangements. In fact, just 40% of adults saw an NHS dentist in the two years to March 2024, compared to 49% before the pandemic. For new patients seeking NHS dental care, the situation is dire – surveys have found that in some areas almost 97% of NHS dental practices aren’t accepting new patients. Part of the problem is that there are enough dentists in absolute numbers, but most dentists now do more private work because NHS contracts are seen as financially unviable. In April 2023 there were about 34,500 dentists in England registered to provide dentistry, but only 24,200 (70%) performed any NHS work in 2023-24. Moreover, the NHS dental workforce had over 5,500 vacancies as of March 2024. The upshot is a crisis in access to affordable dental care – you may have heard stories of people forced to DIY their tooth extractions or travel hundreds of miles for an NHS appointment, which underline the severity. From a health perspective, poor dental access can lead to untreated tooth decay, pain, and wider health issues. Interviewers might bring this up to see if you recognize that the NHS’s challenges extend beyond hospitals and GP surgeries, into areas like dental health which also impact patients’ well-being.

Funding Constraints and Increasing Demand

When discussing NHS challenges, it’s important to consider the financial and demographic context in which these problems occur. The NHS is primarily funded through taxation and has a finite budget each year. Funding constraints over the past decade have made it harder to expand capacity to meet rising demand. While NHS spending has increased in absolute terms, the growth rate was slower in the 2010s compared to historical averages. The UK also spends less on healthcare per person than many comparable countries. For example, in 2022, Germany spent about 55% more per capita on health care than the UK, and France about 26% more. As a share of GDP, the UK’s public health spending (around 10-11%) is middle-of-the-pack among advanced economies. This suggests that limited investment has contributed to some of the capacity issues – fewer doctors, nurses, and hospital beds per head of population – and leaves the NHS less able to absorb shocks like a pandemic or winter crises.

At the same time, demand for healthcare is rising inexorably. Britain’s population is both growing and ageing. People are living longer, which is wonderful, but older individuals often have more complex health needs. The number of people aged over 85 in England is projected to double over the next 25 years, reaching about 2.6 million by the late 2040s. This “ageing population” means more patients with chronic conditions, such as diabetes, heart disease, dementia, and arthritis, who all require substantial care and support. Alongside age, factors like lifestyle-related illnesses (e.g. obesity) and mental health conditions have also increased demand on NHS services.

The combination of tight funding and increasing demand creates a continual challenge: how to do more with limited resources. The NHS has pursued efficiency drives and service transformations (like moving care into the community and using technology) to stretch its budget. Nonetheless, many experts argue that without significant investment – in staffing, equipment, and infrastructure – the NHS will struggle to improve performance. In interviews, you might be asked your thoughts on how the NHS can cope with these pressures. A good answer could mention the need for long-term workforce planning (which the NHS has started with a new 15-year workforce plan), social care reform to ease hospital pressures, embracing innovation, and securing appropriate funding. Importantly, it’s about showing awareness that system-level issues like funding and demographics underpin many of the frontline challenges we see in waiting times and staff shortages.

Example Medicine Interview Questions on NHS Challenges

Interviewers use questions about NHS challenges to assess your understanding, communication, and motivation for a career in medicine. They don’t expect you to be an expert, but they do expect awareness of key issues and an ability to discuss them thoughtfully. Practice responding to questions like these in a structured and clear way, showing balance and insight. Here are 10 example questions related to NHS challenges that you could be asked in a medical school interview:

“What do you think is the biggest challenge currently facing the NHS, and why?” – This open question lets you pick an issue (e.g. staffing or waiting times) and discuss causes and consequences. Ensure you give reasons and maybe mention more than one perspective.

“Ambulance response times have risen dramatically in recent years – what factors are behind this, and how might we improve the situation?” – Here you could talk about increased demand, hospital handover delays, workforce shortages, and ideas like more ambulances or better social care to free up A&Es.

“Why are A&E departments under such pressure, and what do you think could be done to reduce long waiting times in emergency care?” – You should touch on causes like staffing, bed availability, flu/COVID surges, and suggest solutions such as expanding capacity, better primary care access (to prevent unnecessary A&E visits), or improving patient flow.

“The NHS has not been meeting its cancer treatment time targets. What impact do these delays have, and how might the NHS address them?” – Discuss the importance of timely cancer care for outcomes, the stress on patients, and mention measures like investing in diagnostics, hiring more specialists, or using private sector capacity to catch up.

“General practice is said to be in crisis with too few GPs. Why is it hard to get a GP appointment nowadays, and what might improve access to primary care?” – You could explain the GP shortage, increasing patient numbers, and ideas like training more GPs, better retention (making general practice more attractive), and use of other healthcare professionals (nurse practitioners, pharmacists) to support GPs.

“How do staff shortages and NHS workforce issues affect patient care? Can you suggest any ways to tackle the workforce crisis?” – Here you’d connect staffing to morale, waiting times, and patient safety. Solutions might include expanding medical school places, international recruitment (with its pros/cons), improving working conditions to retain staff, and maybe mention the new NHS Long Term Workforce Plan.

“Social care is often mentioned in relation to NHS problems. Can you explain the connection and why fixing social care is important for the NHS?” – In your answer, define social care briefly and talk about how lack of care packages leads to bed blocking in hospitals. Highlight that an integrated approach is needed – funding social care, community services – to relieve pressure on the NHS.

“What challenges exist in NHS dental services, and what does this reveal about the NHS as a whole?” – This allows you to show awareness beyond hospitals. You’d mention the difficulty finding an NHS dentist, the reasons dentists leave the NHS (contract, pay), and how it affects public health (people living with pain). It shows you understand NHS is not just about hospitals.

“In the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, what are the main hurdles the NHS must overcome?” – You could mention the backlog of treatments, staff exhaustion/burnout, the mental health fallout, and possibly financial constraints due to pandemic expenditure. It’s good to acknowledge that the NHS showed resilience but now has to restore services and morale.

“If you were the Health Secretary, what three measures would you prioritise to ensure the NHS is sustainable for the future?” – This invites you to think proactively. Strong answers might include investing in workforce (training and retention), increasing funding or efficiency, integrating health and social care, promoting public health/prevention to reduce future demand, and embracing innovation (like digital health). Be sure to justify each measure briefly.

Remember, when answering questions about NHS challenges, stay calm and structured. It’s fine to take a moment to think. Start with a brief overview of the issue, discuss a couple of key points (causes, impacts, possible solutions), and show empathy where relevant (after all, these challenges affect patients). Interviewers aren’t looking for a policy dissertation – they want to see that you as a future doctor care about the healthcare system and are informed enough to engage in a discussion about it. By preparing on topics like those above, you’ll demonstrate motivation for medicine and a realistic understanding that being a doctor involves working within the NHS system, challenges and all.

Sources:

NHS England and parliamentary reports on NHS performance

British Medical Association and King’s Fund analyses on workforce and waiting times

Public Accounts Committee report on NHS dentistry and NHS Confederation coverage of NHS statistics and patient experiences.

These authoritative sources underline the facts and figures discussed above, and they can be useful for further reading as you prepare for your interviews. Good luck with your preparation – understanding these NHS challenges not only helps you succeed in the interview, but will also deepen your appreciation of the healthcare environment in which you aspire to work.