What to Do If You Don’t Get Into Medical School

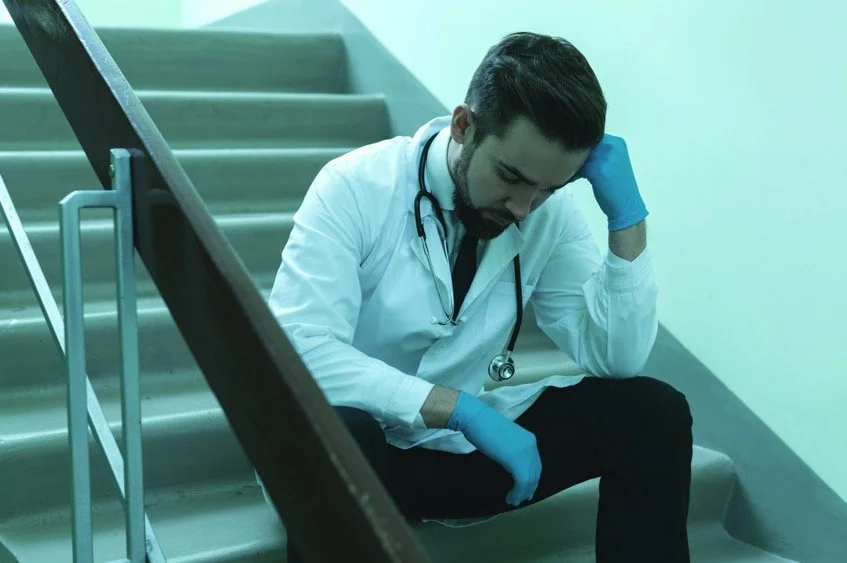

Keep Perspective and Reflect on Your Application

Not getting into medical school can feel devastating, but you are far from alone. Medicine is one of the most competitive courses – thousands of qualified applicants are turned away each year due to limited places. In 2024, for example, over 24,000 students applied for roughly 7,600 UK medical school places. It’s no reflection on your worth or potential as a doctor. Getting into medical school is highly competitive, so although you may be disappointed not to get a place, you won’t be alone. Many excellent candidates have to apply more than once.

Take a moment to breathe and regroup. After the initial shock, reflect on why your application might have been unsuccessful. Ask yourself:

Did I apply to universities that matched my academic profile (grades, admissions test scores)?

Was my UCAS personal statement as strong and tailored as it could be, or could I have spent more time refining

Did I gain enough relevant work experience or volunteering to demonstrate my commitment to medicine?

If I was rejected before interviews, did I meet all the minimum requirements and apply strategically to suitable schools?

If I were rejected after interviews, could I improve my interview technique or better answer specific questions next time?

How did I perform on the UCAT/BMAT admissions tests – did I practice enough and do I need to improve my score?

If I had a conditional offer but missed the grades, were there extenuating circumstances, and do I think I could do better if I retake some exams?

Honest answers to these questions will help you identify areas to strengthen. Seek feedback from teachers or career advisers on your application if possible. Understanding what went wrong is the first step to making a stronger comeback.

Importantly, consider whether you still feel strongly about pursuing medicine. It’s normal to feel discouraged, but take time to confirm that becoming a doctor is truly what you want. If it is, great – there are multiple pathways forward. If you realise your passion lies elsewhere, that’s okay too; there are many fulfilling careers in science and healthcare beyond medicine. The key is to form a plan, stay motivated, and not view this as the end but rather a detour on your journey.

Check for Last-Minute Opportunities: Reserve Lists & Clearing

Before moving on to longer-term plans, make sure you’ve explored any immediate options to secure a spot in a medical program this year:

Near-Miss and Reserve List Offers: Some medical schools will accept applicants who miss their offer conditions by a small margin, depending on how many total spots are filled. For example, if you were required to get AAA and achieved AAB, a university might still take you if they have capacity. Similarly, a few schools maintain waiting lists (reserve lists) of strong candidates. If you were put on a reserve list after interviews, stay alert – medical schools may contact waitlisted applicants on Results Day to offer a place, and you’ll need to decide quickly. Keep your phone on and email inbox monitored around the time of the results. Ensure UCAS has your up-to-date contact details, and check your UCAS Track on results day to see if any “unconditional” acceptance appears unexpectedly. It does happen for a lucky few.

UCAS Clearing: If Results Day has come and you have no offers confirmed, you can see if any medical schools have places available through Clearing. Clearing is the UCAS process that matches unplaced students to course vacancies from July through October. However, medicine vacancies in Clearing are extremely scarce due to the strict caps on medical school numbers. Most years, few (if any) medical schools have Clearing spots because they fill all seats in the primary cycle. In 2022, reportedly no standard-entry medicine courses were in Clearing at all, while 2023 and 2024 saw a handful of schools unexpectedly open a small number of Clearing places. There’s no guarantee any medicine courses will be in Clearing in a given year. If they are, you must still meet the typical entry requirements (high grades, UCAT/BMAT scores). Clearing does not lower the bar for medicine. Universities will also likely conduct rapid interviews for Clearing applicants.

Action step: If you choose to pursue a Clearing place, be prepared: monitor the official UCAS Clearing listings starting on results day, and act fast. Medical Clearing spots can literally fill within hours or minutes of being announced. Have your results, UCAS ID, personal statement, and a short explanation of why you’re a great candidate ready to discuss. Start calling universities first thing on Results Day morning if you see a vacancy. Our detailed guide “A Guide to Medicine Through UCAS Clearing 2025” explains how to navigate this process and which schools have offered Clearing places in recent years (and is updated for 2025 entry) – be sure to check it out for step-by-step Clearing advice (what documents you need, timing, contact strategies, etc).

Keep in mind that Clearing for medicine is a long shot. You should never bank on Clearing as your primary plan to get into medicine – it is a last-resort option. By all means, seize the opportunity if it arises, but have a backup plan (such as a gap year) since most applicants will not find a Clearing place. The same goes for reserve lists: hope for the best, but plan for the worst.

Take a Gap Year and Reapply

One of the most common paths for students who don’t get into medical school on the first try is to take a gap year and apply again in the next admissions cycle. Thousands of students do this every year – for 2024 entry, 3,580 applicants were reapplicants trying again after a previous attempt. Many eventually succeed on their second or third try. Medical schools do not penalise reapplicants, and you’ll come back stronger with more experience.

That said, a gap year should be used wisely. This is your chance to address any weaknesses in your prior application and become an even better candidate:

Boost your grades (if needed): If you fell short of the required A-level grades, you could consider resitting one or more exams. However, be aware that not all medical schools accept A-level resits, and some that do will expect higher grades from retake applicants. For example, a university that usually asks for AAA might require A*AA from a student who took an extra year to achieve the grades. Check each target medical school’s policy on resit applicants before proceeding. If you do plan to resit, register early for your exams and maintain a structured study schedule during your gap year to improve your marks. You can combine part-time study with other activities (work or volunteering) so you aren’t just stuck at home with textbooks.

Gain more work experience: Use the year to get meaningful experience in healthcare settings. Seek a job as a healthcare assistant, medical receptionist, pharmacy tech, or any role that gives exposure to patient care and the NHS. Many reapplicants work as care assistants in nursing homes or hospitals, or take on an NHS Healthcare Support Worker role – earning money while getting valuable experience and talking to patients. You can also do volunteering – for example, with St. John Ambulance, the British Red Cross, a local hospice, care home, or charity for the elderly or disabled. Medical schools love to see sustained commitment to caring roles. These experiences will strengthen your understanding of healthcare and provide excellent material for interviews and your UCAS personal statement.

Volunteering or community work: If formal work is not feasible, regular volunteering still shows dedication. Consider volunteering in a hospital, care home or clinic, or even non-healthcare volunteering that develops your communication, teamwork, and empathy. For instance, volunteering at a youth group, tutoring, or working with a charity can help build transferable skills to discuss at an interview.

Shadowing and medical insight: If possible, arrange some doctor shadowing or medical insight weeks (your school or career adviser may help, or try contacting local hospitals/GP surgeries). Shadowing doctors can reinforce your motivation and give you more to talk about regarding the realities of a medical career. Even virtual work experience programs or online courses related to healthcare (like a first aid course or an online MOOC about health) can be helpful to expand your insight.

Improve your admissions test scores: If your UCAT was not competitive, dedicate time to prepare thoroughly and re-take the exam. Many students see significant score improvements after an extra year of practice. Use question banks, take mock tests under timed conditions, and consider a prep course if needed. A higher admissions test score will open up more medical school options next time.

Enhance your UCAS personal statement: With new experiences under your belt, you can write a much stronger UCAS personal statement. Use your gap year activities to demonstrate maturity, commitment, and growth. Show how you’ve turned disappointment into determination. Having a year to reflect can also help articulate more convincingly why you want to do medicine and why you’ll be a great doctor.

Practice interview skills: If you reached the interview stage previously or anticipate interviews next time, use the gap year to practice. Seek mock interviews – some charities and services help medical school applicants with free mock MMIs/panels. Stay updated on NHS hot topics and ethical scenarios. The confidence gained from an extra year of preparation can make a big difference.

One advantage of reapplying after a gap year is that you will apply with achieved A-level grades (if you’re not resitting) rather than predictions. This can be reassuring to schools and may slightly strengthen your application. However, remember that even with significant improvements, medicine will still be competitive. There is no guarantee of acceptance the second time around, so it’s wise to have a backup plan in case. Nonetheless, plenty of students are accepted on a later attempt – perseverance is often part of the journey in medicine.

Finally, be sure to apply smartly when you reapply. Research entry requirements and apply tactically to schools that align with your strengths. For example, some medical schools place a heavy weight on UCAT – if your UCAT is great, target those; if not, maybe apply to BMAT schools or those that consider academics more. Use tools like the Medical Schools Council entry requirements guide or admissions statistics to inform your choices. And don’t apply to the same four universities if they weren’t a good fit the first time; cast a wider net (including some slightly less oversubscribed programs or those with schemes for reapplicants or widening participation, if relevant to you). By learning from your first round and bolstering your profile, you can significantly increase your odds of success on the next try.

Pursue a Different Degree and Graduate Entry Medicine

Another route to becoming a doctor is to complete an undergraduate degree in a related subject and then apply to medicine as a graduate. Many students take up their “Plan B” degree (often the 5th UCAS choice on their application) after not getting a medicine offer, intending to later pursue Graduate Entry Medicine (GEM). This path is longer and requires commitment, but it’s a standard solution for determined future doctors.

Here’s how it works: you would enrol in a different but relevant degree – for example, Biomedical Science, Biomedical Engineering, Medical Physiology, Pharmacology, Neuroscience, or even something like Chemistry or Psychology – basically, a science or health-related subject you enjoy. After obtaining your bachelor’s degree (typically in 3 years), you apply to a graduate-entry medicine program, which is usually a 4-year accelerated medical degree for graduates. The UK now has about 16 graduate-entry medicine programmes (A101 courses) designed for students with a first degree. These allow you to become a doctor in four years instead of the standard five, but they pack the content more intensively. Alternatively, graduates can also apply to standard 5-year medicine courses (A100) – that route is slightly longer overall, but sometimes a bit less pressure per year.

Things to consider with the graduate entry route:

Academics: You’ll need to perform very well in your first degree. Graduate medicine programs typically require at least a 2:1 honours degree (upper second-class) for eligibility. Some even ask for a minimum of a high 2:1 or specific grades in certain subjects. If academics were a challenge at A-level, be mindful that you’ll need to step up your game at university. Choose a subject you are genuinely interested in and capable of doing well in – it shouldn’t just be a “means to an end.” You will be studying it for 3+ years, so make sure you find it engaging. And remember, getting a 2:1 or First isn’t easy; university is a step up from school, especially if you choose a rigorous science course.

Admissions tests and requirements: Graduate-entry medicine programs often have their own entrance exam requirements. Many require the GAMSAT (a specific test for graduate med applicants), while some accept UCAT. You’ll also need to write a new personal statement (or equivalent) and possibly attend interviews when you apply to GEM, similar to undergraduate admissions. Some programs expect or prefer your first degree to be in a life science subject, though others accept any discipline. Research the specific requirements of GEM courses before committing to your undergraduate choice, so you don’t inadvertently make yourself ineligible for your target graduate programs.

Competitiveness: Be aware that graduate-entry medicine is highly competitive as well – in fact, even more competitive in some ways. There are far fewer GEM places available (only a few hundred nationally, since not every med school offers a graduate program), so the applicant-to-seat ratios can be very high. For example, a GEM course might have 20 seats for several hundred graduate applicants. You will be up against other very motivated candidates (many of whom also didn’t get into undergrad medicine and went on to excel in their degrees). On the positive side, by the time you apply as a graduate, you’ll have more maturity and experience – and you can use your years as an undergrad to build a stellar CV (volunteering, research, leadership in university societies, etc.). Just proceed with realistic expectations: this path is not an easier back door into medicine; it’s just a longer alternative route.

Finances: A crucial factor is funding. Unfortunately, student loans do not fully cover the cost of a second degree in medicine in the UK. Currently, graduate medical students have to self-fund a portion of their tuition and living expenses. For 4-year GEM courses in England, typically in Year 1, you get no tuition fee loan (you pay the first ~£9,250 out-of-pocket, though a maintenance loan for living costs is usually available). In Years 2-4, a portion of your tuition may be covered by the NHS bursary, but you still have to pay some of it (and maintenance support via loans/grants may be limited). This means you might graduate with more debt or need to find financial support. It’s essential to research the latest funding situation and be prepared for the financial commitment of doing two degrees. By contrast, if you went straight into another field or career, you might avoid that extra cost. So think carefully about the monetary aspect of graduate entry.

Transfers and alternate paths: In a few cases, universities offer the chance to transfer into medicine after the first year of a related degree, but these opportunities are rare and highly competitive. For example, a few medical schools allow top-performing students in Biomedical Science or similar to apply for a transfer into Year 2 of the MBBS. But there are no guarantees and often only a handful of transfer spots (some years, none at all). If you go into your first degree hoping to transfer, make sure you would be happy completing that degree and applying to GEM, because a direct transfer is statistically unlikely. Treat it as a bonus possibility, not a given plan.

Choosing the graduate entry route is essentially “playing the long game.” It requires patience and determination – you’re looking at possibly 7-8 years of education before you qualify as a doctor (3 years undergrad + 4 years GEM, plus the mandatory 2-year UK Foundation Programme after medical school). The upside is you get to experience university life right away in another subject, rather than taking a year out, and you’ll broaden your knowledge by studying a different field. Many who go this route say the perspective they gained from another discipline was valuable in making them well-rounded medics. If you remain focused, work hard in your degree, and keep your medical dream alive throughout, graduate entry can absolutely lead you to becoming a doctor. Just weigh the pros and cons carefully – it’s a valid Plan B for those who are certain medicine is their end goal and are willing to invest the extra time and effort.

Consider Studying Medicine Abroad

If you didn’t secure a UK medical school place, another avenue is to study medicine in another country. Each year, some determined students choose to enrol in medical schools overseas (for example, in Europe, Asia, or the Caribbean) that offer programs taught in English. Entry to UK medical schools is so competitive that a rising number of students decide to study medicine abroad and attend universities overseas. Countries like Poland, Romania, Bulgaria, Hungary, and Italy (among others) have become popular destinations for British students pursuing medicine. These schools often have lower entry requirements or simply more capacity for international students.

Studying abroad can be an exciting adventure. You’ll get to live in a different country, experience a new culture, and perhaps even learn a new language, all while working toward your medical degree. In your clinical rotations, you’ll witness healthcare in a different system and gain a broader perspective on medicine. Some students find that studying abroad helps them develop independence and resilience. And importantly, you’ll still be moving forward with your goal of becoming a doctor, just via a less conventional route.

However, there are important considerations before leaping overseas:

Accreditation and Quality: Not all foreign medical schools are created equal. You must ensure the school you attend is recognised by the UK General Medical Council (GMC) as providing an acceptable medical degree. Otherwise, you may not be able to practice in the UK afterwards. The good news is that many universities (especially in the EU) are recognised, but do your homework – check the World Directory of Medical Schools and the GMC’s guidance on overseas qualifications. Avoid programs that seem “too good to be true” or lack proper accreditation.

Language and Examinations: If the program is taught in English (as many in Europe are), you won’t have to learn an entire new language for classes, but living in a foreign country usually means picking up the local language for day-to-day life, which can be a rewarding challenge. More critically, when you finish your degree abroad, you will need to pass licensing requirements to practice in the UK. All doctors who qualify outside the UK must demonstrate their knowledge and skills, typically by taking licensing exams (such as the UKMLA, which is replacing PLAB, by the time you graduate) and an English language test if English isn’t your primary language of instruction All doctors intending to practise in the UK are required to be registered with the GMC, and international medical graduates must usually pass exams to show they meet UK standards and can communicate effectively. This means even after completing medical school abroad, you’ll have additional steps before starting work in the NHS. It’s absolutely doable – many overseas graduates succeed each year – but it’s an extra hurdle to plan for.

Cost and logistics: Studying medicine abroad can be costly for UK students. Some countries have lower tuition fees than the UK, but others (or private universities) can be equal to or higher than those in the UK. Plus, you have travel costs and possibly learning a new healthcare language or taking extra exams. You might not have access to UK student loans for overseas programs, so funding needs careful consideration. Additionally, being away from your support system of family and friends can be challenging – factor in the emotional and mental adjustment.

Future training: If your ultimate plan is to return to the UK for postgraduate training, know that you will usually need to come back and compete for UK Foundation Programme jobs after you finish your degree. UK medical graduates get the first allocation to those junior doctor training posts. As an international graduate, you would typically apply in the open competition for any remaining slots (though UK nationals graduating abroad are often considered favourably). In recent years, most overseas grads who pass the exams and apply have been able to obtain an FY1 post, but specialities beyond that can be competitive. It’s just something to keep in mind long-term.

Despite these challenges, many students have successfully pursued medicine abroad and gone on to become doctors in the UK. If you’re considering this path, research thoroughly. Look at forums, speak to current students or alumni of those international programs, and verify the outcomes (do their graduates get licensed and employed in the UK or other countries?). Check if the universities have agencies or representatives in the UK who can guide you through the application. And be prepared to be adaptable – moving abroad at 18 or 19 is a big step.

In summary, studying medicine abroad is a viable option if you didn’t get into a UK school, but weigh the pros and cons. It can keep your dream alive without a gap year and offer unique life experiences. Just ensure you understand the extra steps required to eventually practice in the UK, and choose a reputable medical school that will set you up for success. If you have the passion and flexibility, this path can still lead you to the same goal: becoming a doctor.

Explore Other Healthcare Careers (Allied Health Paths)

As you weigh your next steps, it’s worth remembering that being a doctor is not the only way to have a fulfilling healthcare career. You may have been so focused on medicine that you haven’t explored the many other roles through which you can help patients and make a difference. Nursing, midwifery, dentistry, pharmacy, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, paramedic science, physician associate, radiography, biomedical science, and a wide range of other allied health professions are all vitally important and rewarding fields to consider.

Take some time to research these options:

Allied Health Professions: The NHS employs a vast variety of health professionals. For example, physiotherapists help patients recover movement and manage pain; occupational therapists empower people to live independently after illness/injury; radiographers perform imaging that doctors rely on for diagnoses; speech and language therapists help patients with communication or swallowing issues; dietitians advise on nutrition for health; paramedics provide frontline emergency care; podiatrists specialize in foot and ankle health – the list goes on. These careers typically require degrees (often three-year programs), but the entry requirements can be more attainable than medicine, and the education is highly vocational. If your passion is patient care, many of these roles could satisfy that desire to work in healthcare.

Nursing and Midwifery: Nursing is a challenging and respected profession, working closely with patients in all areas of medicine. Nurses have increasing autonomy (advanced nurse practitioners can even prescribe medications and run clinics). Midwifery focuses on caring for mothers and babies through pregnancy and birth. These degrees might appeal if you enjoy direct patient contact and a caring role, but in a slightly different capacity than a doctor. The NHS is actively recruiting nurses and offers financial support, such as bursaries for nursing degrees.

Dentistry or Pharmacy: These are distinct professions from medicine, but are similarly esteemed and might align with your interests in science and patient care. Dentistry leads to becoming a dentist, focusing on oral health and surgery – it’s competitive as well, but some students who initially aimed for medicine find their calling in dentistry. Pharmacy is about medicine use and optimisation – pharmacists are medication experts who work in hospitals or communities to advise on and dispense medications. Both require specific degree programs (BDS for dentistry, MPharm for pharmacy) and have their own application processes. Still, if you haven’t considered them, they could be alternatives where you apply your love for medical science.

Psychology and Mental Health: If your interest leans toward mental health, consider psychology or related fields. A psychology degree could lead to roles in clinical psychology (with further training), or other mental health professions like therapy or psychiatry-adjacent careers. The psychological therapies field (counsellors, therapists, clinical psychologists) can be incredibly impactful.

Biomedical Research and Life Sciences: Perhaps you enjoyed the science of medicine more than the idea of clinical practice. In that case, a degree in biomedical science or molecular biology might lead you to a career in research, academia, or industry (biotechnology, pharmaceuticals). You could contribute to medical advances from the lab side – developing new treatments, diagnostics, or gaining a deeper understanding of diseases. Some students realise they prefer the idea of medical science to medical practice, and that’s an important insight.

If you decide to pursue an allied health or alternative career, you’re not “giving up” – you’re finding the path that fits you best. The NHS and healthcare sector are multidisciplinary; doctors are just one part of the team. Remember that being a doctor isn’t the be-all and end-all of working in healthcare. You can have a fulfilling career improving patients’ lives in many other roles. The work-life balance and training pathways in some other health careers can be more favourable. It’s all about where your passion and skills lie. So, explore these options with an open mind. You might discover a career that excites you as much as (or more than) being a physician.

Final Thoughts: Stay Determined and Positive

Facing rejection from medical school is tough, but it can also be a turning point. Many successful doctors have stories of initial setbacks – what matters is how you respond. By seeking feedback, improving your qualifications, and exploring alternative routes, you are already demonstrating the resilience and determination characteristic of a great doctor.

If medicine is truly your calling, don’t give up. Whether you take a year out to strengthen your application or pursue a different path and come back to medicine later, you can still achieve your goal of becoming a doctor. It may take a bit more time or an unconventional route, but those who persevere often find the journey enriching. Every experience you gain along the way – be it working in healthcare, studying another subject, or living in a new country – will shape you into a more skilled, empathetic, and worldly clinician in the future.

On the other hand, if during this process you discover that another career excites you more, that’s a valuable realisation too. There is no shame in changing direction if you find something that suits you better. Your happiness and sense of purpose in your career are what ultimately matter.

In summary, not getting into medical school is not the end – it’s a setback that you can overcome. You have numerous options: try for a spot through Clearing if available, reapply with a stronger profile after a gap year, take up a related degree and aim for graduate entry, study abroad, or channel your talents into a different healthcare field. Whichever route you choose, approach it with optimism and determination. Learn from this experience, work on your weaknesses, and come back even stronger. Many before you have walked this road and still achieved their dream of becoming a doctor.

Finally, remember to take care of yourself during this period. Surround yourself with supportive family and friends, stay engaged in activities you enjoy, and keep your end goal in sight. This challenge can make you more resilient – an attribute you will carry into medical training and practice. Good luck, keep your head held high, and know that your journey to a medical career is still very much alive. With hard work and the right plan, you can and will find your place in the world of medicine.

Frequently Asked Questions – What to Do if You Don’t Get into Medical School

1. How can I reflect effectively on my unsuccessful medical school application?

Reflection is essential if you want to turn a rejection into a future offer. Break down your application into key stages: academic record, UCAT or BMAT score, personal statement, work experience, and interview performance. Identify specific areas for improvement—did you meet the minimum entry requirements? Was your admissions test score competitive? Did your interview answers fully demonstrate your motivation and suitability for medicine?

Where possible, ask for feedback from the universities you applied to, and keep detailed notes. By analysing your performance honestly, you can create a clear action plan for your next application cycle.

2. What are reserve lists and Clearing, and can they lead to a place?

Some medical schools use reserve lists to manage strong applicants when places are limited. If a place becomes available due to a withdrawal or a student not meeting their offer conditions, it may be offered to someone on the reserve list. If you are on one, keep your contact details up to date and be ready to respond quickly to an offer.

UCAS Clearing is another route, although places for medicine in Clearing are rare and in very high demand. Occasionally, vacancies arise due to unexpected dropouts or lower-than-expected uptake. Monitor the UCAS Clearing listings closely and be prepared to contact universities immediately if a place becomes available.

3. Should I consider reapplying next year, and how can I strengthen my application?

Yes, many students gain a place on their second attempt. To strengthen your chances:

Boost your grades – resit exams if you fell short of entry requirements.

Raise your admissions test score – dedicate focused time to UCAT/BMAT preparation using practice questions, mocks, and expert guidance.

Expand your work experience – volunteer in healthcare settings, shadow doctors, or work in patient-facing roles to deepen your understanding.

Improve interview skills – practise with mock MMIs or panel interviews to refine your answers and confidence.

A gap year can be a valuable opportunity to grow your skills and knowledge before reapplying.

4. What is Graduate Entry Medicine, and is it an option for me?

Graduate Entry Medicine (GEM) is a four-year programme for applicants who already hold a degree. It’s an excellent option if you want to pursue another subject first or build your academic record before reapplying to medicine. GEM entry is competitive, often requiring strong grades, relevant work experience, and an additional admissions test such as GAMSAT.

Choosing a related undergraduate degree, such as biomedical sciences, nursing, or pharmacy, can keep the door open for GEM applications in the future.

5. Are there allied healthcare or overseas medical courses worth considering?

Absolutely. If you’re passionate about healthcare, allied health professions can be fulfilling and rewarding careers. Consider degrees such as nursing, physiotherapy, radiography, paramedic science, midwifery, or physician associate studies—all of which offer opportunities to make a real difference to patient care.

Some students choose to study medicine overseas, in locations such as Europe or the Caribbean, where entry requirements may differ. Before applying abroad, check that your degree will be recognised by the General Medical Council (GMC) if you intend to practise in the UK, and research the costs, teaching language, and licensing process.